Finance Capital Vs. the New Generation

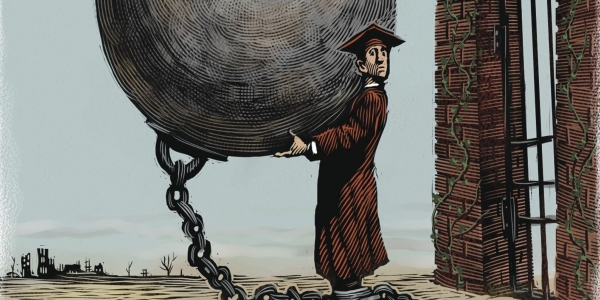

Tim Foley for The Chronicle

By Jennifer M. Silva

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Brandon, a 34-year-old black man from Richmond, Va., labels himself "a cautionary tale." Growing up in the shadow of a university where both his parents worked in maintenance, he was told from an early age that education was the path to the "land of milk and honey." An eager and hard-working student, Brandon earned a spot at a private university in the Southeast—finally, his childhood dream of building spaceships seemed to be coming true. He shrugged off his nervousness about borrowing tens of thousands of dollars in loans, joking: "Hey, if I owe you five dollars, that's my problem, but if I owe you $50,000, that's your problem."

But his light-hearted banter belies the long train of obstacles and uncertainties that have followed him at every turn. Unable to pass calculus or physics, Brandon switched his major from engineering to criminal justice. He applied to several police departments upon graduation, but he didn't land a job.

With "two dreams deferred," Brandon took a job at a women's-clothing chain, hoping it would be temporary. Eleven years later, he's still there, unloading, steaming, pressing, and pricing garments on the night shift. When his loans came out of deferment, he couldn't afford the monthly payments and decided to get a master's degree in psychology—partly to increase his chances of getting a good job, and partly, he admitted, to put his loans back in deferment. He finally earned a master's degree, paid for with more loans from "that mean lady, Sallie Mae."

So far, Brandon has not found a job that will pay him enough to cover his monthly loan and living expenses, and since the clothing company recently cut overtime and bonuses, he is worried. He keeps the loans in deferment by continually consolidating—a strategy that he said cost him $5,000 a year in interest. Taking stock of his life, Brandon is angry: "I feel like I was sold fake goods. I did everything I was told to do, and I stayed out of trouble and went to college. Where is the land of milk and honey? I feel like they lied. I thought I would have choices. That sheet of paper cost so much and does me no good. Sure, schools can't guarantee success, but come on—they could do better to help kids out."

Brandon, like many blue-collar millennials, is stuck on a journey to adulthood with no end in sight. His own parents, who had just high-school degrees, were married, steadily employed at the college, and homeowners well before they reached his age. But working-class kids today are growing up in a world where taken-for-granted pathways to adulthood are quickly eroding. Since the 1970s, stable blue-collar jobs have rapidly disappeared, taking family wages, pensions, and employer-subsidized health insurance along with them. Unlike their parents and grandparents, who followed a well-worn path from school to the assembly line—and from courtship to marriage to childbearing—men and women today live at home longer, spend more time in school, change jobs more frequently, and start families later.

Working-class men and women have come to see their relationship with college as a broken social contract.

The answer to the time-honored question, "What do you want to be when you grow up?"—or, more aptly, "What can you be when you grow up?"—is in flux. And as working-class families have grown more fragile, and communities, churches, and neighborhoods less close, men and women find themselves on their own when it comes to piecing together an adult life amid the isolation, uncertainty, and insecurity of 21st-century American life.

I spent two years interviewing 100 working-class 20- and 30-somethings in Lowell, Mass., and Richmond. I spoke with African-Americans and whites, men and women, documenting the myriad obstacles that stand in their way. Caught in a merciless job market and lacking the social support, skills, and knowledge necessary for success, these young adults are relinquishing the hope for a better future that is at the core of the American Dream.

They believe wholeheartedly that the only way out of dead-end jobs is a college degree. But over and over again, I heard stories of bewilderment and betrayal. They lack the skills and knowledge they need to navigate an increasingly complex, costly, and competitive higher-education system. Whether confused about majors, stymied by bureaucracy, crippled by loan debt, or left feeling like they don't belong, working-class men and women have come to see their relationship with college as a broken social contract. As they see it, they bought into the promise of higher education but got nothing but disappointment and loss in return.

The losses are not only economic but also emotional. After graduating from high school, Rebecca, the daughter of a coal miner, enrolled at a state university, hoping to become a teacher. But she was put on academic probation after only a year because her high school had not adequately prepared her for college work. "I struggled. I was all freaked out about writing," she said in a strained voice, reliving the panic and humiliation of her first semester of college.

During her sophomore year, Rebecca's college dreams continued to unravel: "I ended up plagiarizing my paper, so I can't go back. And it wasn't even intentional. I had a disk with notes and pieces from the Internet, you know, all on there to write my paper. And I plugged in a paragraph of somebody else's words that I didn't mean to do. A counselor was like, you can probably get out of this if they know all the circumstances, but I was an emotional mess, so I didn't even go back to see him."

Feeling too overwhelmed to fight her way through the university bureaucracy, Rebecca dropped out of college, moved back in with her parents, and found restaurant work, which she has been doing ever since. When working-class students make mistakes, even out of ignorance, there is no one to fight for them or cushion the fall.

Sometimes this sense of disappointment and confusion crosses the line into anger, leaving these young people feeling cheated by a system that was supposed to support them. Amber, a 28-year-old white woman who works in a bakery, revealed: "I knew I was smart and that I wasn't a straight-C student, yet all my teachers—you know, we had 30 kids in the class, and the teachers were just too busy ... unless you were destructive, you really didn't get attention. Once I knew that I had ADHD, knowing if somebody had seen it in me earlier, I could have gotten so much further. If somebody had just known. ... Sometimes I feel cheated out of life. I could have been in college by now. I could have had a real live career that is not just a cook."

Of course, it may be simplistic to believe that a diagnosis would have changed the course of her life so drastically. But in her eyes, it is the source of her current struggles, the reason why the month always ends in a "search for change to buy ramen."

Working-class young people realize that they don't have the tools and resources to succeed in college. They don't have anyone to fight for them—no parents making phone calls to the principal, no tutors helping them study for exams, no counselors testing them for learning disabilities.

Though they feel betrayed and angry, strangely, their anger doesn't make them want to fight the system. Rather, they want to succeed in it, against the odds and on their own.

They make a virtue out of self-sufficiency, embracing the ethos of competition and individual achievement that is at the heart of the American education system. Many devise individual solutions to structural obstacles. Amber, for example, turned to self-help books to treat her self-diagnosed ADHD. She has learned to rely only on herself.

By taking sole responsibility for their fate, working-class youth resolve the contradiction between their high expectations and their disappointing reality. And that makes sense, given their inability to navigate bureaucracy and their fundamental distrust of others.

Returning to Brandon, who can't quite let go of the American Dream of buying his "own piece of land" and landing "a 9-to-5 with a salary," we can see how the ethos of individual achievement slides into self-blame. "My biggest risk is myself," he said. "I don't want to leave or just take another job even though I could. I limit my opportunities too much. I hold on too much to what I have. I don't want to uproot my life for a job because pulling up the stakes is too much to handle." He blames himself and his unwillingness to take risks as his greatest barriers to success.

Most disturbing, these men and women feel the need to compete against others in the same dire circumstances as themselves. Brandon ended our conversation with this lesson: "I was just arguing with a girl on Facebook about whether all people should be able to go to college for free. I don't want that because then my degree would be worthless. In the real world, success is about having more tools than the next man." Divided, distrustful, and alone, they keep playing a game where the odds are stacked against them, hoping to somehow come out ahead.

There is more than one side to every story, of course, and we don't know from these men and women about the people who helped them, or the working-class kids who do succeed despite the odds. But what we can see is that mere access to higher education isn't enough to close the widening gap between the haves and have-nots in this country. Working-class kids are stuck between hope and bitterness, anger and self-blame. Without knowledge of how particular majors lead to jobs, or the confidence to ask for help, the skills to demand responses, and the support to persevere, working-class kids interpret their experiences in college through a lens of betrayal when they leave it, having learned only to put their dreams on hold.

Jennifer M. Silva is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School and the author of Coming Up Short: Working-Class Adulthood in an Age of Uncertainty, just out from Oxford University Press.

![[PDA - Heathcare NOT Warfare - Sign the Petition.]](http://pdamerica.org/images/ads/HealthNotWar_final.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment